How Does GPS Work? GPS for Dummies

Almost everyone understands that GPS uses satellites to pinpoint our position on earth. Whether you have a GPS unit or use a smartphone with GPS, understanding some of the principles behind how it works will help you feel confident when using or purchasing one. In this guide, I'll demystify GPS using plain language and then share some tips to get the most out of your GPS.

- How Does Your GPS Work?

- How A GPS Figures Out Where You Are

- Getting More Accuracy From a GPS

- Practical GPS Tips For Better Performance

GPS is Satellite Based Radio

When people say "GPS" they are referring to a system of navigation that pinpoints your position on earth by using signals from radio satellites orbiting the earth. All you need to get your position is a GPS receiver. Almost all smartphones have a GPS receiver built-in today. A GPS receiver does not transmit any signals, all it does is receive GPS data beamed to earth from GPS satellites. If you can't receive the GPS signals, you can't get your position.

Each GPS unit, regardless of size, has a small chipset and GPS antenna. GPS signals are received via the antenna and then sent to the chipset, which is the workhorse, decoding the satellite signals, performing multiple calculations based on the GPS information, and then spitting out a location.

GPS is Really GNSS

The acronym GPS (Global Positioning System) is generally used synonymously with the more accurate acronym GNSS (global navigation satellite system). Why? Because GPS was the first worldwide satellite positioning system, started in 1993 by the US Government (now run by Space Force). GPS was originally conceived by the Department of Defense for the military, but since its launch in 1993, has been leveraged by users worldwide.

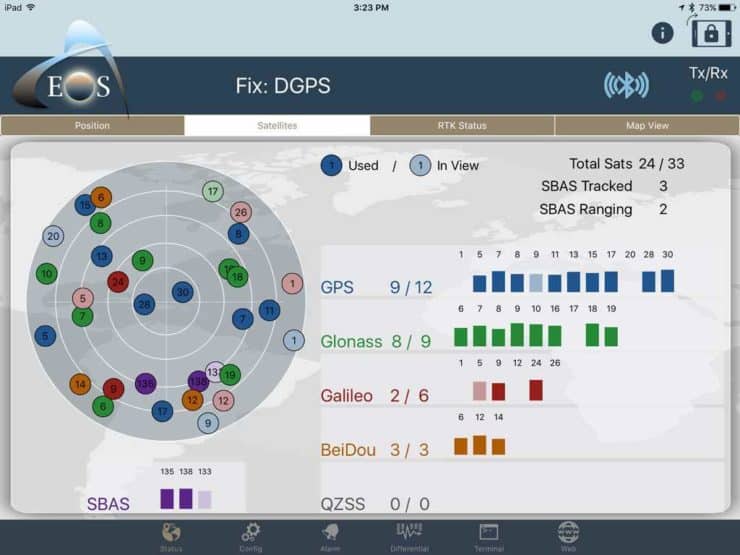

Since then other countries have gotten in on the act, launching their own GNSS systems. And for each GNSS system, new satellites are being launched all the time, and the technology in them continues to improve. Although each GNSS has it's own particulars, they all work on the same fundamental principles that I'll cover in this guide.

| System | Country | Satellites | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPS | USA | 33 | global |

| GLONASS | Russia | 27 | global |

| Galileo | EU | 30 | global |

| QZSS | Japan | 7 | Asia |

| IRNSS | India | 7 | Asia |

| BeiDou | China | 27 | global |

It should also be noted that these are the GNSS systems that are publicly available. Other countries (I'm looking at you UK) have been rumored to have their own GNSS systems that are only available for military use. And commercial satellites such as Elon Musk's StarLink will be able to augment current positioning systems (from an accuracy of 300cm to 70cm) and maybe even work on its own as a GNSS.

Want to know what GNSS systems that your Android phone can receive? Try the GPSTest app. For iPhones, you have to go to the specs page on Apple.

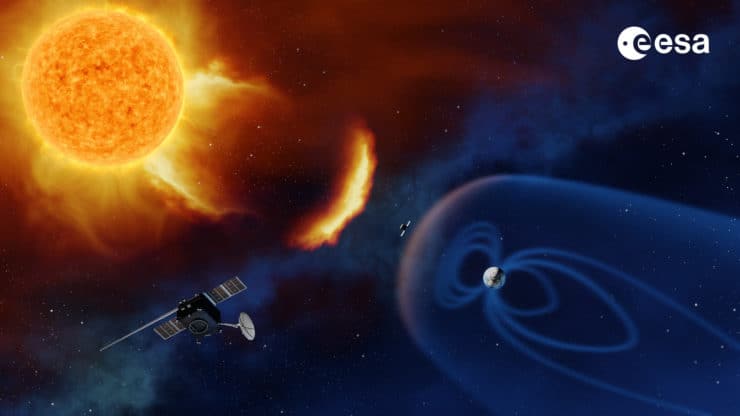

The GPS Signal

If you're familiar with AM or FM radio, you know that stations have a radio frequency. For example, in Southern California, you can tune your car radio into KPCC public radio on FM 89.3, or 1070 KNX on AM. GPS signals are similar, but instead of AM or FM, they are on something called the L-Band, which roughly lies below the band used for AM radio. Why the L-Band? Because this set of radio frequencies can penetrate clouds, fog, rain, storms, and vegetation with minimal interference (more on that later). The idea is that it works anywhere.

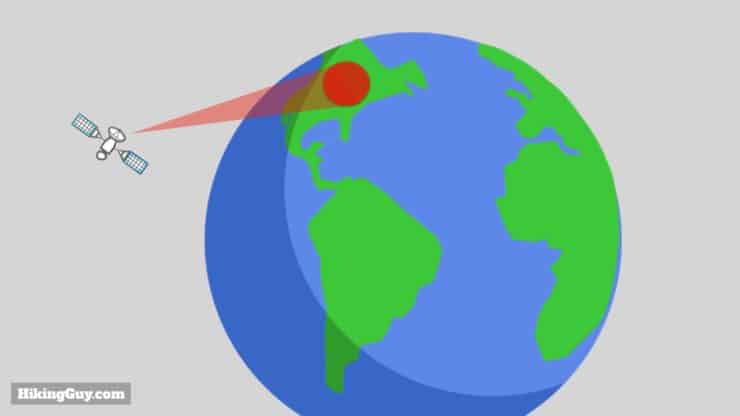

The actual GPS signal is a series of "ons" and "offs" in a specific format that gives your GPS receiver information about the satellite, the time the signal was sent, and the satellite's position. Your GPS unit not only receives this information, but also measures how long it takes the signal travel from the satellite to your receiver, at the speed of light, to determine the distance between you and the satellite. This measurement of elapsed signal travel time is key to getting accurate measurements.

In order for a GPS to work correctly, the times must be synchronized across all the positioning signals. To put the importance of correct time in context, a 0.001 second error equates to a 300km inaccuracy. So each GPS satellite has an atomic clock, the most stable and accurate time reference ever developed (using the element Rubidium most of the time), and it uses that clock to broadcast its time. Atomic clocks in satellites are expensive ($50-100k) and big, but today you can get one for $1500 that fits in your pocket.

Your GPS receiver does not have an atomic clock, but rather a quartz one. In the end, the GPS time doesn't matter much. An accurate atomic time signal is pulled from a GPS signal to synchronize (more in the next section).

How GPS Determines Your Position

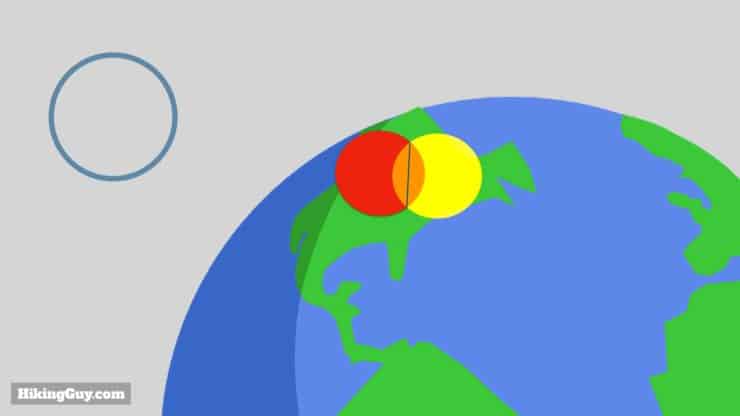

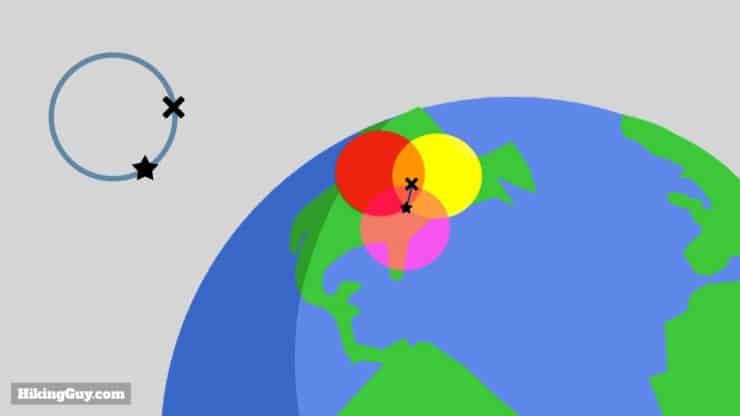

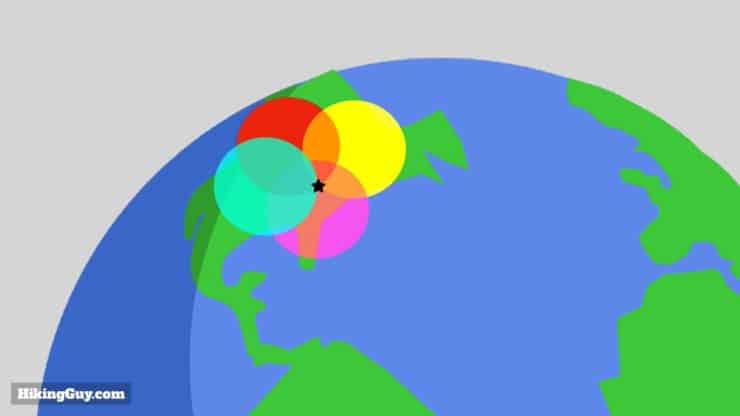

At a minimum, your GPS receiver needs three satellite signals (aka "fixes") to determine your position, which is called trilateration.

Remember the theory of relativity? Because time moves faster for objects with less gravity, like GPS satellites, their clocks get 38 microseconds faster than earth clocks every day. That equates to about 6 miles of accuracy. The GPS system has been programmed to address this, and having a fourth satellite fix helps eliminate timing errors.

Do More Satellites Increase Accuracy?

No and yes. Theoretically, for a 3-D position, you just need 4 signals / spheres. They will all intersect at one point. Adding more spheres will not make that one point anymore of one point. In practice, a GPS chipset will be performing multiple trilateration calculations using different sets of signals, and then using statistical analysis to narrow down that set of positions to a more accurate single position. So having more satellites to choose from, assuming the GPS chipset can handle them, will help.

How Accurate is GPS?

According to the official US Government website for GPS, most consumer GPS units are accurate to a 16 feet radius. On newer multi-band GPS units, you can get a 6 foot accuracy regularly. Other multi-GNSS units usually fall around 9-16 ft. Now how this figure is actually generated is part of the secret sauce in the GPS unit and you have to take that figure with a grain of salt. There are factors that I'll talk about next that can degrade your accuracy, but these are good general figures.

I'm assuming everyone wants as accurate of a GPS fix as possible, but it helps to put GPS accuracy into context. The US Parks Service recommends that trails be built with a minimum width of 4ft. If you're hiking and your GPS is giving you 6-16ft of accuracy, that should be more than enough to help you navigate. It should also be enough to record your track fairly accurately. It's probably not enough to guide a self-driving car without plunging it off a cliff.

And just as important as accuracy is reliability. You want a position accuracy figure that stays constant as you move through canyons, tree cover, and buildings. Newer technology can help keep a reliable fix as you move around. I'll talk about that shortly as well.

What Causes GPS Inaccuracy?

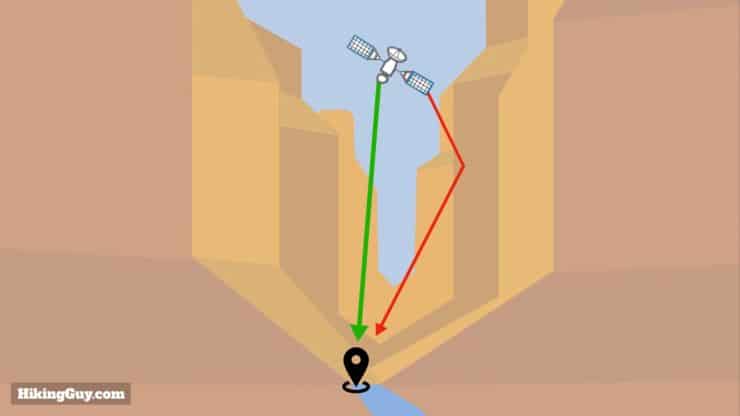

In an ideal world, your GPS unit would receive four perfect GPS signals with no interference, read all the information, and calculate a precise position. But in the real world, there are factors that can degrade the GPS signal as it travels the 12,550 miles from space to earth. The effect of GPS signal interference is bad or incomplete GPS data. A modern GPS chipset will evaluate the quality of the GPS signal and throw out those that are not good. More primitive GPS units will just give you a less accurate position.

Here are the main culprits that can degrade your GPS accuracy.

Can the government reduce the accuracy of a GNSS? Yes. For the US GPS system, there is a feature called Selective Availability that degrades the accuracy. The idea is that the government degrades public GPS when it might benefit an enemy, etc.. It was rarely used in the early days of GPS, and today is "permanently" turned off by law. We all know that laws change, laws are broken, and who knows what the future holds. Other GNSS systems can be degraded as well.

Lastly, you can have hardware or software problems at any point in the process. Sometimes satellites malfunction, or orbits change slightly because of gravitational shifts. When this occurs the GNSS providers broadcast "fixes" for the issues (more later). Satellites can also go down because of malfunctions and service (and you can check their status here).

You can even have software errors on the GPS receiver end. In 2020 many GPS units were off because the Sony GPS chipset didn't account for the fact that the year had 53 weeks. Problems like this are usually addressed through firmware updates, so make sure your unit is up to date.

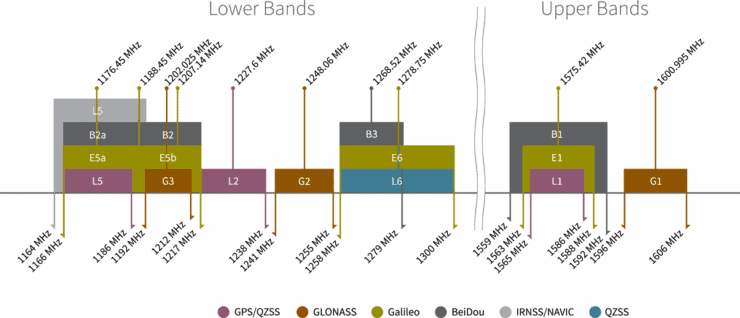

New GPS Bands

I mentioned that the first GPS constellation became operational in 1993. Well since then, technology has progressed and GPS has as well. Today the US is launching the third generation of GPS, aptly named GPS 3. For the GPS end-user, this equates to new GPS bands. Here's what the GPS bands are all about.

| Band | Year Started | Description |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | 1993 | This is the original GPS band. It's the slowest and does the worst job at traveling through objects. |

| L2C | 2005 | It's a newer signal that's more efficiently encoded and penetrates objects better. It's generally combined with an L1C signal which allows it to correct some ionospheric errors. |

| L5 | 2010 | GPS 3 satellites support the L5 frequency which has a stronger signal and is encoded the most efficiently. It's considered "the best" positioning frequency that you can receive outside of encrypted military options. |

| L1C | 2018 | Think of this new signal as a "connector" signal that allows GPS to slot in more efficiently with other GNSS systems. |

New GPS satellites are backward compatible. So GPS 3 satellites not only broadcast L5 signals, but also L1. And not all satellites (as of 2021) support the newer bands.

Overall the newer bands allow signals to travel more efficiently, eliminating a good amount of interference. It means that the GPS unit can get a more reliable signal, ensuring a consistent position with every fix. So while it might also offer a more accurate position, it's really the consistency of a good signal through varying conditions that is the game changer.

GPS Helpers

In an ideal world, your GPS would be 100% accurate, but as you've seen, it's not the reality with the current GNSS systems. So various entities have come up with ways to improve the GNSS positioning experience. Brace yourself of an onslaught of acronyms.

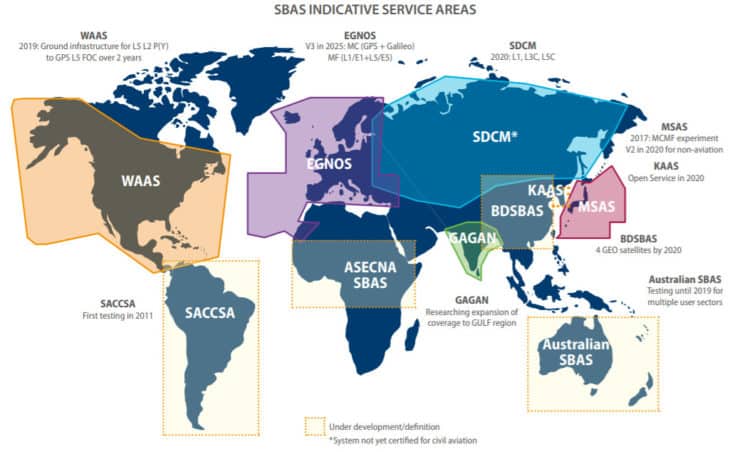

WAAS & Satellite-based Augmentation Systems

Knowing that there can be orbit and timing errors with GNSS satellites, their operators have set up systems to monitors these errors, calculate corrections, and then broadcast the correction to users using a different set of satellites. These are called Satellite-based Augmentation Systems (SBAS), and unlike the global footprint of some GNSS systems, generally only offer coverage in the home area of the operator.

For you as an end user, if you have the option to "enable WAAS" as found on some Garmin units, do it. It can improve the accuracy of your position. Note that receiving this additional signal and applying the corrections will require a bit more power consumption from your GPS chipset.

Assisted GPS (A-GPS or A-GNSS)

When you first power your GPS on, it needs to acquire signals, read the data, and then predict the orbits and positions based on those signals. But the orbit data and corrections for all the satellites is available online as a data feed, so why not grab it from the much faster cellular or WiFi connection first? That's what A-GPS performs.

The result is a much faster initial satellite fix and a small amount of power savings. Most smartphone GPS systems will have this built in, and even standalone GPS units like a Garmin Fenix or handheld will download information when you sync with your phone. On a Garmin they are called EPO or CPE files.

Differential GPS Systems

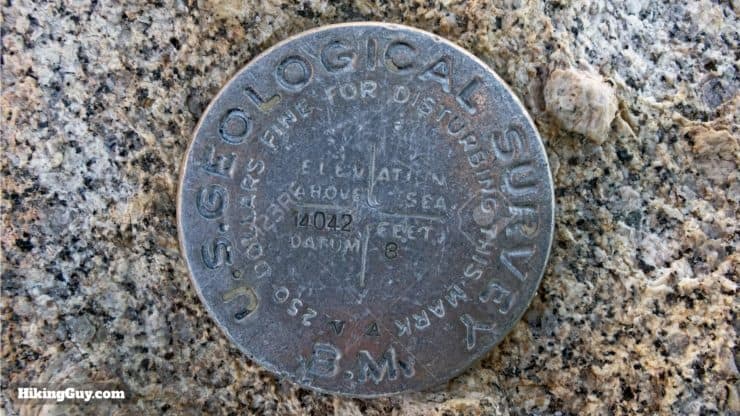

If you know the precise surveyed position of a point, and compare it to your GPS position reading, you would know the offset or difference. Once you knew how far off your GPS was, you could apply the difference to your data to get a precise position. This is called differential GPS positioning. There is a worldwide network of ground stations that monitor GPS differentials and provide that data for free to users (USA and world locations).

The problem is that this differential correction isn't currently something widely supported in real-time, but as communications get more sophisticated, it's not out of the question for a handheld GPS to access this data and apply it. Instead, you can upload your GPS data (saved as a RINEX file, a feature available on newer models like the GPSMAP 66 and Montana 700) to the NOAA OPUS site, and then get back a corrected file. There's other ways to do it as well, but that's the gist of it. It's a fairly technical process, but hopefully in the future, it could be seamless and integrated into systems like Garmin Explore and Garmin Connect.

The US Coast Guard and Army Corps of Engineers used to broadcast differential information over a radio signal, the Nationwide Differential GPS System (NDGPS). With the advent of WAAS and the new bands, it was discontinued in 2020.

Real-Time Kinematic (RTK)

RTK is the modern version of differential GPS. It uses a sophisticated method to determine satellite error and offset at a base station, and then transmits the offset to roving GPS units. Often the transmission occurs over data networks instead of radio waves. RTK is commonly used by surveying to get a 1cm level of accuracy. It's so precise that RTK base stations are used to measure tectonic plate movement.

RTK receivers can have a cellular connection to access data in the field from base stations. RTK base stations are generally accessed by a paid subscription, but there are some publicly available RTK stations. You can even set up your own RTK base station.

GPS Positioning Today and Beyond

Modern GPS chipsets can receive multiple signals from multiple GNSS systems simultaneously. From there, they can evaluate factors such as the signal quality and strength, pick the best options, and then calculate your position. They can also use different combinations of satellites and signals to simultaneously calculate multiple position fixes and perform statistical analysis to refine them further. As GPS chips become more sophisticated and efficient, the more variables they can evaluate and the more calculations they can perform.

Modern GNSS chipsets determine your position based on

- a combination of GNSS signals

- new GNSS bands

- accelerometer input (also known as pedestrian dead reckoning or user dead reckoning)

- position based on nearby WiFi and Bluetooth signals (works similarly to GPS positioning)

- position based on cellular signals

- real-time atmospheric data and compensation

- 3D mapping of the earth's surface

New smartphones with powerful processors have the computing horsepower to evaluate all of these inputs and offer a very precise position, probably leaving many dedicated handheld GPS units in the dust. For example, newer phones like the Google Pixel 5 can get a GPS accuracy of about 3 feet. If you're hiking, running, or biking, you probably don't need much more precision than the width of your body.

For purpose-built outdoor GPS units from companies like Garmin, it will be tough to compete with smartphones, especially as phones get more rugged and efficient. Moving forward I'd expect standalone GPS to offer universal adoption of the newer GNSS bands, better battery life, and hopefully better chip logic and control. Integrating an RTK component (either in real-time or cached when synced) would also be a great way to out-perform the smartphone. It will be interesting to see how the smartphone GPS versus dedicated GPS battle evolves.

GPS Tips

- If you need to choose between multiple GNSS bands or multi-band signals within one GNSS (like L1 & L2C & L5 in GPS), I've found that the multi-band within one system outperforms multiple GNSS systems.

- One of the main power draws on a GPS unit is the GPS chipset use. If you have the GPS chipset working at full bore, recording every second using multiple GNSS systems, it's going to consume more power. Every GPS unit is different, but the more features that you can "turn off" the less power that your GPS unit will consume.

- Turn on WAAS if you have it and are okay with the battery drain.

- Turn off "smart recording" and enable every-second tracking if you have that option. "Smart recording" uses inputs such as the accelerometer and heart rate to determine what data points to save, but the logic has been known to make bad choices. Setting recording for every second ensures that your position is always saved.

- Sync your GPS with your phone or WiFi before using it. That will download the latest A-GPS files, check for firmware updates, sync your clock, and should allow you to acquire a GPS fix quicker. If you're using the GPS after a long time or after traveling far, this is even more important.

- Turn on your GPS and let it sit with a clear view of the sky for about 2 minutes before starting your tracking. This is called GPS Soak and gives the unit time to get a stable position.

- Carry your GPS unit on a shoulder strap or top pocket, giving it a clear line of sight to the sky.

- If you are buying an InReach GPS device, you probably won't see GLONASS support. The InReach (Iridium) and GLONASS frequencies are close to each other, and transmitting in InReach would interfere with the GLONASS reception (or maybe even fry the receiver). In fact, on InReach devices like the GPSMAP 66i, the unit supports GLONASS but the software has it disabled.

- Calibrate your compass and barometer if your device has them. These can be inputs for your GPS chipset.

- On Android devices, turn on "high accuracy" mode by going to settings > location > mode > high accuracy.

- On Garmin devices, enable 3-D speed and distance, which factors in elevation changes when calculating distance and speed. It should give you more reliable tracking data.

- Pause your GPS when you stop. Why? Because if you have say, 10ft of accuracy, and you're recording every second, each fix can be 10 feet away, recording about 600 ft of travel over 1 minute when stopped. This is called GPS nesting or drift.

Basic GPS Concepts in Use

Need More Info?

- Have a question about the guide? Join my Patreon and ask me a question.

In-Depth Garmin GPSMAP 65s Review & Guide

In-Depth Garmin GPSMAP 65s Review & Guide What is a GPX File?

What is a GPX File? Garmin GPSMAP 66i Review & Guide

Garmin GPSMAP 66i Review & Guide Garmin Fenix 6 In-Depth Review

Garmin Fenix 6 In-Depth Review How To Get Free Garmin GPS Maps For Hiking

How To Get Free Garmin GPS Maps For Hiking Garmin GPSMAP 66sr Review & Test

Garmin GPSMAP 66sr Review & Test How to Hike

How to Hike Garmin Fenix & Epix

Garmin Fenix & Epix Garmin inReach

Garmin inReach Best Hiking Gear 2024

Best Hiking Gear 2024 Hiking Boots or Shoes: Do I Really Need Hiking Boots?

Hiking Boots or Shoes: Do I Really Need Hiking Boots? When to Hit SOS on inReach

When to Hit SOS on inReach